Collection

When it was established in 1925, Murney Tower Museum, then Kingston’s only museum, was tasked with sharing the story of our city. Today, we proudly continue this tradition by interpreting an extensive collection of objects that paint a detailed picture of Kingston’s past. Our collection has evolved over the decades, but today consists of over 1300 artifacts, divided into three main collection areas: the Gardiner Collection, the McGregor/McIntyre Collection, and the General Collection. These collection areas represent a number of different aspects of Kingston’s history, from its time as a British military stronghold to the domestic lives of residents in the early twentieth century. Taken together, the collection tells the captivating, conflicting, and sometimes troubling history of Kingston.

General Collection

As the oldest operating museum in Kingston, Murney Tower was once the only place for residents to donate items of historical importance. Collected over the course of several decades, the General Collection consists of an eclectic mix of artifacts that encompass various aspects and periods of Kingston’s history. It highlights our community’s desire to tell its own story.

Kingston was long thought to be the birthplace of hockey, and while it is now believed that hockey was invented in England, hockey and ice skating have a long history as popular pastimes in our city. As such, artifacts like this pair of ice skates, which are believed to have been handmade circa 1824, are important to our community’s past and present.

In order to use this stereoscope, a stereograph (a card with two nearly identical pictures on it) would be placed in the device. When a viewer looked through the lenses, the pictures would appear as one, three-dimensional image. In the nineteenth century, it was the only way for people to view the wonders of the world from the comfort of their own home.

This colourized photograph, likely taken in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, depicts the locks and bridge at Kingston Mills. Although this photograph captures a tranquil and leisurely scene, the construction process of the Rideau Canal was anything but. At Kingston Mills alone, around one hundred workers were infected with malaria, and thirteen were killed by the disease.

This waffle iron was manufactured between 1910 and 1934 by the Taylor-Forbes Company. Founded in Guelph in 1902, the company marketed their waffle iron design as “superior to all others for simplicity, durability, and service.” Given the similarity of the design to our 21st-century waffle irons, we can trust that this advertisement was accurate!

This barometer, a common household item, was used to measure changes in air pressure, allowing the device to forecast short-term changes in weather. This type, an aneroid barometer, uses a small metal box held together by a spring. Small changes in air pressure cause the box to expand or contract, causing the needle to shift to either Stormy, Rain, Change, Fair, or Very Dry.

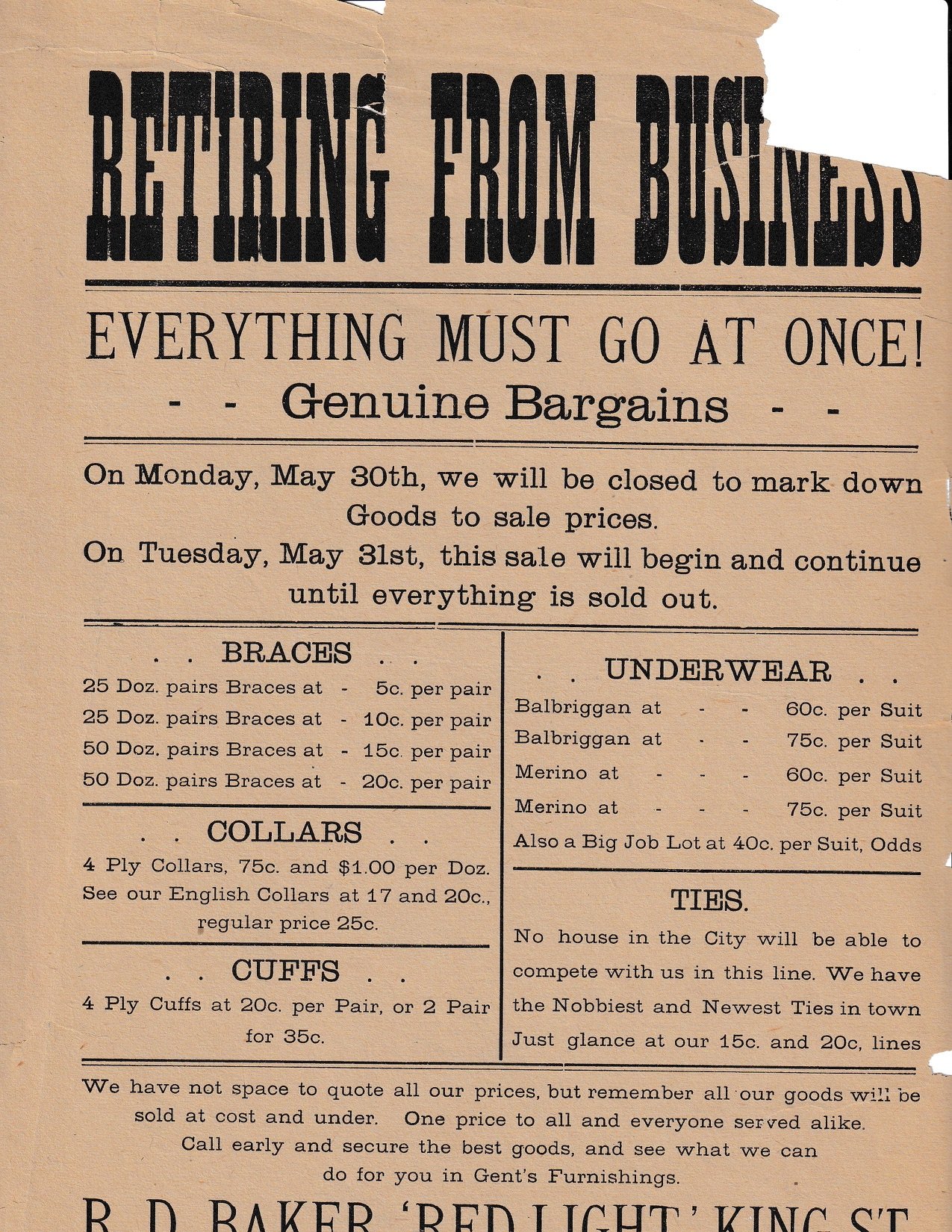

Located on King St. E and mentioned in old city directories, R.D. Baker’s business offered a variety of men’s clothing, from collars to cuffs to ties and more. This flyer advertises the closing sale of R.D. Baker’s store, which was active in the 1890s, and reminds us of the long-forgotten businesses which used to be familiar sights on Kingston’s streets.

This booklet, titled “First Aid for Sick Animals,” was published by Dr. George W. Bell’s Wonder Medicine Company. Dr. Bell established a veterinarian clinic on Brock Street in 1893, and his “Wonder Medicine” was marketed as a panacea for animals. His reputation was destroyed in 1936 when the FDA discovered that the so-called “wonder” mixture was actually over 60% alcohol!

While on one hand a simple tool for the sole purpose of opening envelopes, commemorative letter openers like this one were also an avenue for artists to express their skill and creativity through engravings and illustrations. This particular letter opener, originally from a department store in Edinburgh, commemorates the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911.

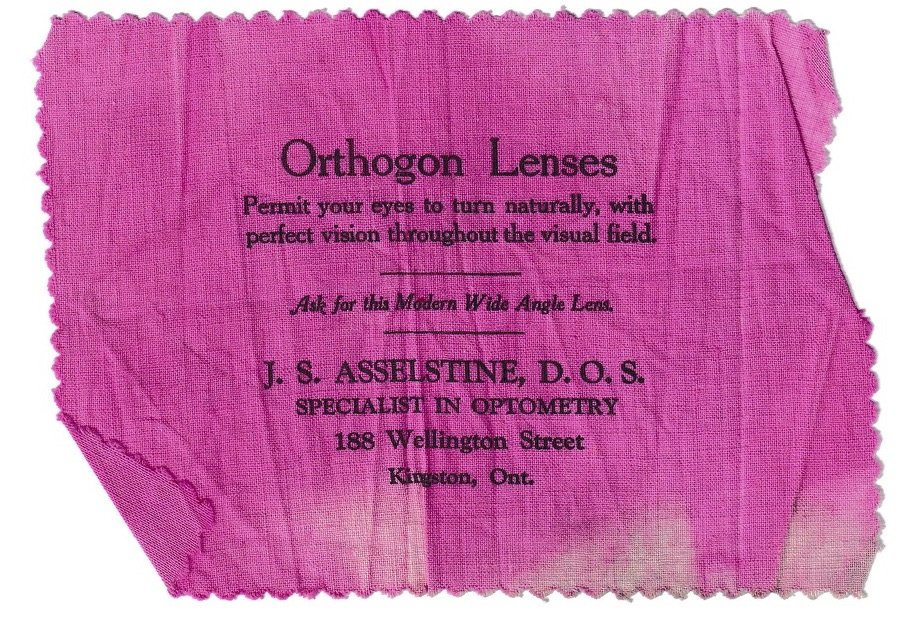

This cleaning cloth didn’t just serve the purpose of keeping your eyeglass lenses spotless – it was also an advertisement for a local Kingston optometry store located at 188 Wellington Street, led by optician and optometrist J.S. Asselstine. From 1916 to 1917, this was Kingston’s only exclusive optical store and featured frequently in advertisements in the Kingston City Directory.

In 1844, Louis Philippe, King of the French, visited Windsor as the guest of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. This silver chain necklace was designed to commemorate this special visit, which was the first time a reigning French king had visited England since the fourteenth century. The faces of both royals are engraved on the front of pendant, while the back details the event.

Although this artifact may look like any old metal bucket, it actually served a very specific purpose: fabric dyeing. This lathe-spun brass kettle, which dates to the second half of the nineteenth century, was especially preferred for dyeing, since using an iron kettle would alter the colours. Dyes were easily made from vegetable matter, such as butternut bark or horseradish.

Stereographs allowed people in the nineteenth century to travel to faraway lands from the comfort of their home. Using a stereoscope, the left- and right-eye images would converge into a single, three-dimensional image. This stereograph depicts a photo of Horseshoe falls and was taken by William Notman, a renowned Scottish-Canadian photographer.

The history of Kingston’s transit system dates back to 1877, when the Kingston Street Railway was introduced as a horse-drawn system for Kingston residents to travel around town. For five cents, this transportation token allowed for a ride on a horse-drawn train car. The transit system, electrified and renamed, operated until destroyed by a fire in 1930.

Crafting flowers out of wax was a popular pastime for Victorian middle-class women. These wooden tools were used to make wax flowers and would be dipped in molten wax, producing a thin sheet of wax suitable for petals and leaves. The art of wax flower making was a means of showcasing a woman’s skill and social status in the Victorian era.

This photograph depicts Shoal Tower, one of Kingston's Martello towers, located directly offshore from Confederation Park and City Hall. This location gave the tower a commanding field of fire over Kingston’s commercial harbour and the entrance to the Rideau Canal. The lack of the conical roof suggests the photograph was taken in the early days of the tower’s construction.

This three-legged cast-iron trivet would be placed underneath a flat iron to keep the heated surface from touching the ground. The name “trivet” is derived from the Latin “tripes,” meaning three-footed! The fact that this trivet is cast, rather than wrought, dates it to the second half of the nineteenth century or the early twentieth century.

A wintertime journey by coach or buggy in the nineteenth century would not be complete without a foot-warmer tucked under your feet for warmth. Foot-warmers were standard household equipment and would be filled with hot coals on the hearth before being taken to the sleigh or wagon – an essential companion for any journey in our harsh Canadian winter.

Hands on the reigns and feet on the pedals, a young child would have peddled this horse and buggy tricycle around their home. In the 1800s, this new version of the traditional nursery horse toy came onto the market, a tricycle with wheels and pedals – which also make the legs of the horse appear to trot.

This communion token has a special link to Kingston’s past, issued in 1823 by St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church. This token, made of pew, provided church members entrance to communion. The use of such tokens was first recommended by John Calvin in 1560 and became widespread. St. Andrew’s, now almost 200 years old, remains on Clergy Street today.

This simple bottle has a hidden origin, found among the cargo items of a sunken ship at the bottom of the St. Lawrence River in the 1800s. Local scuba divers uncovered the shipwreck and unearthed its cargo, which included many glass bottles – not to mention a considerable quantity of wine and liquor, which was sampled by many of the divers!

The original alarm clock, the notes of the bugle would mark the beginning of a day for a soldier living in Murney Tower. This tin bugle has hammer marks on its surface, suggesting that it was made by hand during the first half of the nineteenth century. Originally used as animal horns, bugles in the eighteenth century were bent for use as a military signal.

Pocket watches were popular from the sixteenth century onward, with an attached chain that allowed them to be secured to a waistcoat or belt loop. This silver, 11-by-5 centimetre pocket watch has black Roman numerals on its china surface and likely belonged to a local Kingston resident in the nineteenth century.

McGregor/McIntyre Collection

Donated to the museum in 1970 by Mrs. W. Bruce McGregor, the McGregor/McIntyre collection consists of items from the estate of Miss Margaret McIntyre. The McIntyre family were notable members of the Kingston community in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through a diverse range of artifacts, from war medals to silver objects, this collection captures the McIntyre family’s achievements, heartbreaks, and everyday lives.

Though beautiful to look at, this silver thimble would not have been much use for sewing as the soft silver could be easily punctured by a steel needle. Rather, the thimble and its monogrammed, velvet-lined case served as a symbol of the McIntyre family’s wealth.

This International Order of Allied Mothers in Sacrifice medal, which was granted by the Associated Kin of the Canadian Expeditionary Force to mothers who lost their children in the Great War was bestowed on Margaret Ann McIntyre for the loss of her son, Lieutenant Douglas Neil McIntyre. Lieutenant McIntyre, was killed on November 8, 1917 at the Battle of Passchendaele.

The Gardiner Collection

The Gardiner collection provides a glimpse of the history of the British royal family through the lens of stunning collectible items bequeathed to us by Miss Mary Aleda Gardiner. Miss Gardiner, a teacher in the Kingston area for over thirty years, was gifted her first piece of Victorian China in the 1960s, and her collection of royal commemorative pieces grew rapidly to over 177 items by the late 1970s. Today, Murney Tower Museum is proud to uphold Miss Gardiner’s passions for education and history through this collection.

This beautiful, emerald green jug was made in order to commemorate Queen Victoria’s 1897 Diamond Jubilee, which celebrated her 60th year on the throne. The jug was made by WT Copeland and Sons, the name given to Spode pottery between the mid-nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries.

What is perhaps most interesting about this platter, which commemorates the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria, is that while the grey transfer print decorations include symbolic designs, such as the figure of Britannia in the centre, many of them are informative. While expressing a strict attention to detail and a proud interest in the empire, it also reflects a keen desire for practicality.

This cream pitcher commemorates the May 12, 1937 coronation of King Edward VIII – a coronation which never took place. Although Edward was scheduled to be crowned on this date, he abdicated the throne in December of 1936 in order to marry Wallis Simpson, an American divorcée.

This plate commemorates a local celebration of the Coronation of George V and Queen Mary on June 22, 1911. The centre of the plate displays two portraits of the royal couple with the coat of arms of the Borough of Darlington, where the ceremony took place, in between. Below is an image of a roasting ox, a traditional method of celebrating a coronation.

This cream-coloured, gold-rimmed sugar bowl commemorates Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee – the 60-year anniversary of her reign. Decorated with the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, it was manufactured by Macintyre & Co., a pottery company based in Burslem, England. In 1913, its pottery studio was re-founded as W. Moorcroft Ltd, which still exists today!

This tapestry commemorates the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1887, the fiftieth anniversary of her accession to the throne. An embroidered Queen Victoria features in the centre of the tapestry, flanked by the lion and unicorn of the royal coat of arms, as well as the flags of the British Empire. These celebrations showcased the queen’s role as the “grandmother” of Europe.

In 1897, Queen Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee. This pitcher commemorates the highly anticipated event, marking Victoria as the longest-reigning monarch of Britain. The artifact highlights the portrait of the Queen, who is surrounded by faded gold engravings. The reverse side displays an orange blossom, the flower that the queen wore at her marriage to Prince Albert.

This glossy black teapot with gold detailing commemorates Queen Victoria’s Royal Jubilee in 1887. The Queen’s portrait is encircled by a gold label with flowers that reads “The Royal Jubilee 1887.” To the right of the portrait is a vase with the initials VR (Victoria Regina) containing three orange and white flowers, the petals of which are painted on to give texture to the teapot.

Queen Alexandra and King Edward VII (r. 1901-1910) feature on this intricately designed ashtray. The receptacle highlights the insignia of British royalty, while the ashtray itself is in the shape of a maple leaf, a definitive symbol of Canada. It can therefore be seen as representative of the interconnection of Canada and the UK after nominal independence in 1867.

Collection Stories

Check out some blog posts about our collection items!